exploring the topic of intentional weight loss and why many don’t recommend it.

As someone who was once entrenched in diet culture, I totally get that this might sound crazy. But hear me out.

Diet culture tells us that weight loss = improved health. Plain and simple. No ifs ands or butts about it.

Not only is this not necessarily true, but it significantly discounts how nuanced weight science is. There is often very little we can do to actually control where our weight falls long-term.

First off, we have to accept that every single individual has a unique setpoint weight (or really, weight range). This is a weight range at which our bodies are most happy, productive and healthy. There’s no “right” setpoint weight range — it is different for every individual.

Maintaining this weight is not something your body takes lightly. The further we stray from this setpoint weight range, the harder our body will work to get us back to it. Internal regulation systems work tirelessly to maintain stability for us (which includes keeping us at our natural, healthy weight). When we try to exert outward control on those systems, things go haywire.

There are a number of biological mechanisms in place to reverse efforts of intentional weight loss. Our brain receives constant signals from our fat cells, our digestive tract, signals stimulated by physical activity, our emotions, how we slept, etc. The brain takes all of this information and determines what chemical messengers and nerve responses are appropriate to send out (i.e. ‘eat more,’ ‘eat less,’ ‘move more’ or ‘move less’). It is these things, not our willpower or intention, that control how hungry we feel from one moment to the next.

All of this is to say, there are so many factors and processes going on internally that dictate our hunger, satiety, appetite, weight, metabolism, etc (not to mention numerous external factors such as our environment, mental health, access, etc.). We are not fully in control of these things and no amount of willpower or desire for thinness will change that. Sure, you might be able to override those signals short-term, but your body makes it as difficult as possible for you to stick with that in the long run (especially while maintaining your physical health and sanity). Remember, our body wants to survive, protect us and keep us safe; dieting and restricting is in complete contrast to those goals.

Have you ever gone on a diet, dropped weight only to gain it all back (and maybe then some)? Maybe you’ve even done this a few times throughout your life.

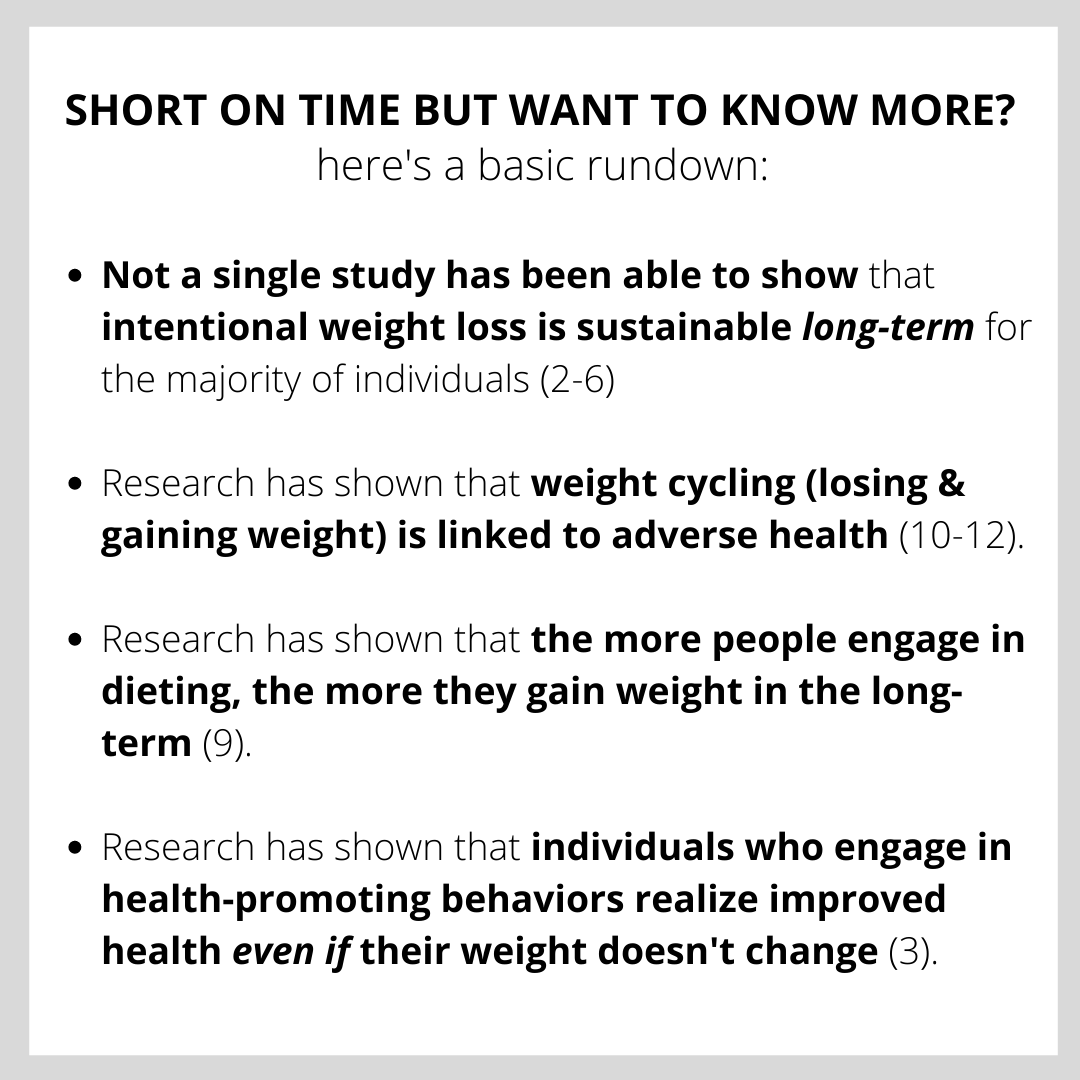

If you nodded your head “yes” to the above, please know that the weight regain was not your fault. You didn’t ‘fail.’ It wasn’t for lack of trying, desire, willpower, or whatever else diet culture will tell you. It’s that intentional weight loss, for the majority of people, just isn’t sustainable long-term (2–6). In fact, one study estimated that no more than 20% of participants who complete weight-based lifestyle interventions maintain the weight loss one year later (7) and there is often an even further drop in that percentage by year two (3). A meta-analysis looked at structured weight loss programs in the US and found that participants regained 77%, on average, of the weight they lost by year five (8). Not only is weight re-gained for most, but it is also now well established that the more individuals engage in dieting, the more weight they gain over time (9).

Here’s the thing: weight loss can occur as a side effect of engaging in health-promoting behaviors, that’s not discouraged or looked down upon. What is discouraged is the idea that we should intentionally try to lose weight through behaviors such as food restriction and/or intense exercise in an effort to seek better health. The research shows over and over again that this is just not successful long-term for any but a small minority of people (and many of those who have “success” doing this report living a life that revolves around food, exercise and their weight).

When and if the research can show that intentional weight loss is sustainable long-term, recommendations will change. But as it stands right now, not a single study has been able to show that intentional weight loss is sustainable long-term for most individuals.

As I mentioned before, our bodies are set up to maintain a stable weight. They don’t respond well to the yo-yo effect that dieting tends to have on weight (losing and gaining over and over). In fact, research has shown that weight cycling is linked to adverse health (10–12).

Given that weight-cycling has the ability to harm our health & well-being, prescribing intentional weight loss cannot be seen as ethical (where an ethical cornerstone held by all healthcare practitioners is ‘above all, do no harm.’). And that’s not even to mention the harmful effects dieting can have on our relationship with food, our minds and our bodies. Dieting also causes us to stress about our food choices, about our exercise routines, about our bodies, etc. and a high stress load harms our health. Any way you slice it, dieting and restricting ultimately tends to do more harm than good.

It’s not abnormal if reading this makes you feel defeated or disappointed. It’s completely normal to mourn the loss of or feel sad to let go of the life you imagined weight loss could bring you.

But here’s the good news: you can improve your health, regardless of whether or not you lose weight. Partaking in gentle, health-promoting behaviors makes a difference in your health even if you don’t see a change on the scale. And better yet? It means breaking free from all those restrictive rules and guidelines. Breaking free from the guilt of overeating after you’ve restricted, from obsession over macros, calories, fat grams and carbohydrates, from constantly worrying what you should be eating or how you should skip going out to go to the gym instead, etc.

We have been taught to believe that weight loss and improved health go hand in hand. That if you’re not seeing the weight on the scale decrease, your efforts are for naught. But that is not true. Research has shown that individuals who engage in health-promoting behaviors realize improved health even if their weight doesn’t change (3).

One last note: making peace with food and coming off the diet cycle is wonderful, and I hope that I can help everyone achieve that. However, I also understand that it doesn’t remove the weight bias and stigmatization that exists in this world. Life for thinner individuals tends to be more convenient, kind, accessible, etc.

That said, the way to generate change around this cultural disposition is not to force those in naturally larger bodies to change their genetic makeup. It’s to create a culture that accepts a wide range of body shapes and sizes. It’s to continue pushing a weight-inclusive over a weight-normative approach, where everybody can achieve health and wellness (independent of weight), and is given access to non-stigmatizing health care. It will take all of us working together to change this, but together, we can achieve it.

References:

- Bacon, Linda. Health At Every Size. BenBella Books, Inc.. Kindle Edition.

- National Institutes of Health (NIH), “Methods for Voluntary Weight Loss and Control (Technology Assessment Conference Panel),” Annals of Internal Medicine 116, no. 11 (1992): 942-49.

- L. Bacon, J. S. Stern, M. D. Van Loan, and N. L. Keim, “Size acceptance and intuitive eating improve health for obese, female chronic dieters,” Journal of the American Dietetic Association, vol. 105, no. 6, pp. 929–936, 2005.

- R. W. Jeffery, L. H. Epstein, G. T. Wilson et al., “Long-term maintenance of weight loss: current status,” Health Psychology, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 5–16, 2000.

- R. R.Wing and S. Phelan, “Long-term weight loss maintenance,” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, vol. 82, no. 1, pp. 222S–225S, 2005.

- Nordmo, M, Danielsen, YS, Nordmo, M. The challenge of keeping it off, a descriptive systematic review of high‐quality, follow‐up studies of obesity treatments. Obesity Reviews. 2020; 21:e12949.

- R. R.Wing and S. Phelan, “Long-term weight loss maintenance,” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, vol. 82, no. 1, pp. 222S–225S, 2005.

- J. W. Anderson, E. C. Konz, R. C. Frederich, and C. L. Wood, “Long-term weight-loss maintenance: a meta-analysis of US studies,” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, vol. 74, no. 5, pp. 579–584, 2001.

- Pietiläinen, K.H.; Saarni, S.E.; Kaprio, J.; Rissanen, A. Does dieting make you fat? A twin study. Int. J. Obes. 2012, 36, 456–464.

- L. Lissner, P. M. Odell, R. B. D’Agostino et al., “Variability of body weight and health outcomes in the Framingham population,” The New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 324, no. 26, pp. 1839–1844, 1991.

- P. Rzehak, C. Meisinger, G. Woelke, S. Brasche, G. Strube, and J.Heinrich, “Weight change, weight cycling and mortality in the ERFORT Male Cohort Study,” European Journal of Epidemiology, vol. 22, no. 10, pp. 665–673, 2007.

- P. M. Nilsson, “Is weight loss beneficial for reduction of morbidity and mortality? What is the controversy about?” Diabetes Care, vol. 31, no. 2, pp. S278–S283, 2008.

Please Note: Statements in this post are meant for general use only and are not intended to diagnose, cure, treat or prevent any disease. Readers are advised to consult with their healthcare providers prior to making any changes to their healthcare management. The information contained in this post is intended to serve as an informational aid and should be used in conjunction with advice from your healthcare professional. It is a supplement, not a substitute, to the knowledge, skill and expertise of healthcare professionals involved in patient care.

6

Amazing piece!! I always trust your material because it is research-based yet still easy to read and understand. Great conclusion as well. These things are truly revolutionary for our culture and I agree that our culture needs to change.

Thank you Ellen! So glad you feel that way about my pieces! And I’m so happy you agree – hopefully all together we can start to make that change! <3